Why the Higgs Discovery Was Physics’ Greatest Detective Story

Precursor: Why the Higgs Story Matters

For more than half a century, physicists chased one gap in an otherwise triumphant theory. The Standard Model (SM) precisely describes quarks and leptons and the forces among them, yet it left a conceptual hole: why are the W and Z bosons heavy while the photon is massless? The Higgs mechanism answered this by positing a scalar field that permeates all of space. Particles interacting with this field acquire mass; particles that do not remain massless. Fluctuations of the field appear as a new particle—the Higgs boson.

Finding it meant creating it fleetingly in proton–proton collisions and inferring its presence from its decay products. LEP and the Tevatron pointed to where it might be, but neither had the energy-luminosity combination to seal the case. The LHC changed the game. With 7–8 TeV collisions and detectors engineered for precision—ATLAS and CMS—the 2012 run finally exposed a new resonance near 125 GeV. The ATLAS paper you’ve likely seen is more than a declaration; it’s a crystallization of theory, detector design, calibration campaigns, and statistical rigor. This post translates that story into a blog format—keeping the physics honest, the math present but light, and the narrative focused on how ATLAS turned noisy collisions into scientific evidence.

The Physical and Mathematical Frameworks (Without the Grind)

Physics. The electroweak sector is a gauge theory with symmetry group SU(2)×U(1). Introduce a complex scalar doublet $\Phi$ with potential:

\[V(\Phi) = \mu^2\,\Phi^\dagger \Phi + \lambda\,(\Phi^\dagger \Phi)^2\]Choosing parameters with $\mu^2 < 0$ yields a nonzero vacuum expectation value (vev) $v$, spontaneously breaking the symmetry while preserving a massless photon. Gauge boson masses scale as:

\[m_W \propto g v, \quad m_Z \propto \sqrt{g^2 + g'^2}\, v\]The physical Higgs boson is the fluctuation around this vev. Its mass $m_H$ is not predicted, but once $m_H$ is assumed, production cross-sections and decay branching ratios are calculable.

Experiment. The Higgs is unstable, decaying almost instantly. For $m_H \approx 125$ GeV, the most incisive final states are:

- $H \to ZZ^{(*)} \to 4\ell$ ($\ell = e,\mu$): tiny rate, exquisite cleanliness, best mass resolution.

- $H \to \gamma\gamma$: rare, but produces a sharp diphoton mass peak.

- $H \to WW^{(*)} \to e\nu\,\mu\nu$: large rate, limited mass resolution due to neutrinos.

| Statistics. Build a likelihood $\mathcal{L}(\text{data}\, | \,\mu,\theta)$ for each channel, where $\mu$ is the signal strength (observed rate / SM rate) and $\theta$ are nuisance parameters (systematics: luminosity, calibration, theory). Use the profile likelihood ratio as the test statistic: |

Translate it into p-values and significances (Z-scores). Combine channels coherently, correlating shared uncertainties. The discovery criterion is $Z \ge 5\sigma$.

ATLAS in One Page: Why This Detector Could Find It

ATLAS wraps the collision point in concentric subsystems. The Inner Detector (pixels, silicon strips, transition radiation tracker) provides precision tracking in a 2 T solenoidal field, crucial for reconstructing electrons and muons and for choosing the correct interaction vertex amidst pile-up. The Electromagnetic Calorimeter (liquid argon) measures electrons and photons with ~1–2% energy resolution, enabling the sharp diphoton peak. Surrounding hadronic calorimeters measure jets and hadronic activity. The outer Muon Spectrometer, embedded in toroids, tracks muons with excellent momentum resolution. A multi-level trigger reduces millions of crossings per second to a recordable stream. Together, these systems are tuned for exactly the objects that Higgs decays yield.

How ATLAS Modeled Reality: Signals, Backgrounds, and Systematics

- Signals. Higgs production via gluon fusion (dominant), vector-boson fusion (VBF), and associated production ($VH,\, t\bar tH$).

- Backgrounds. Channel-specific: continuum $ZZ^{(*)}$ for 4ℓ, QCD diphotons and $\gamma$+jet for $\gamma\gamma$, and SM WW/top/W+jets for WW.

- Systematics. Luminosity (~3–4%), lepton/photon ID, jet energy scale, $E_T^{\text{miss}}$, PDFs. Correlated across channels to avoid double-counting.

The Three Channels That Broke the Case

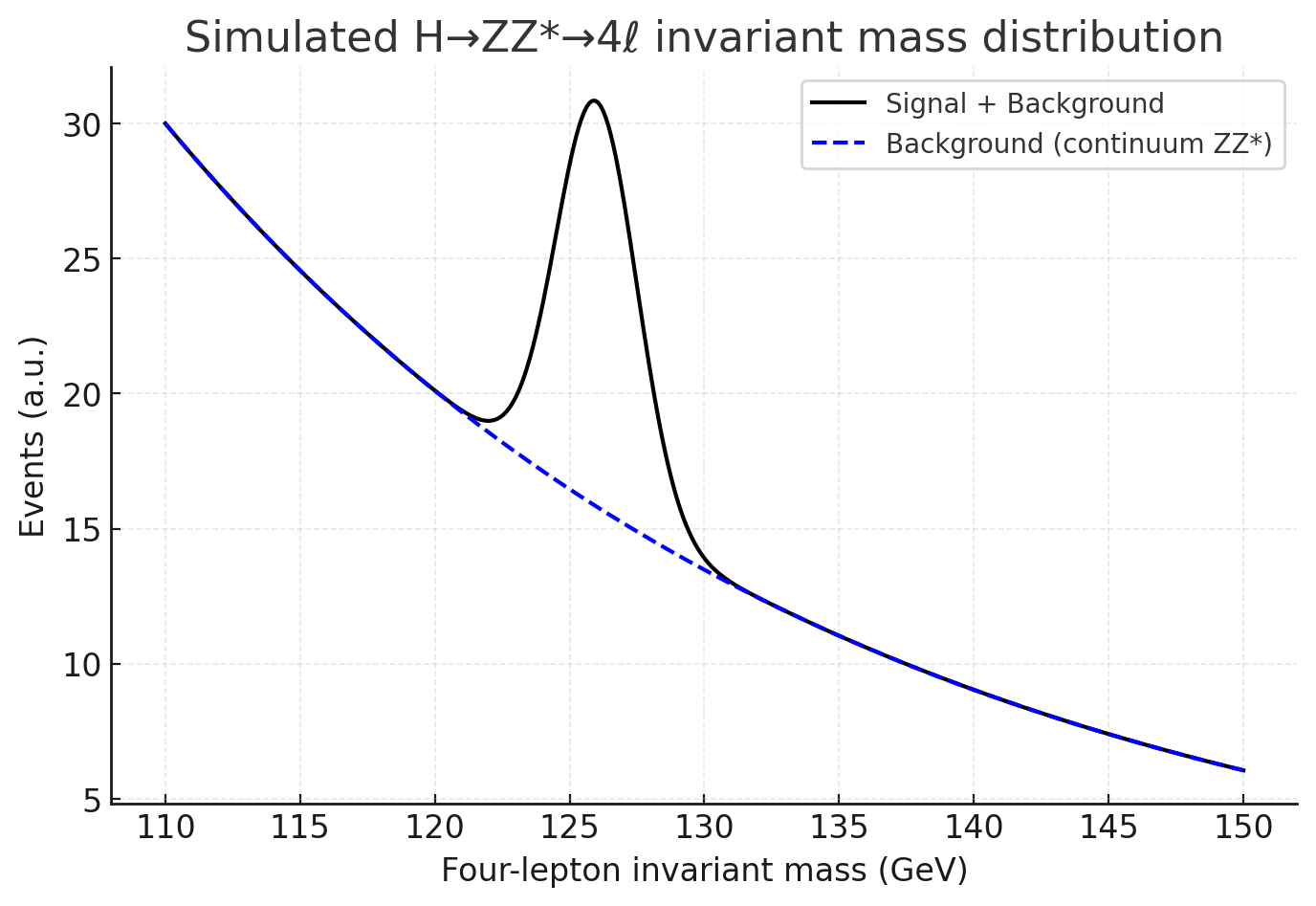

1) $H \to ZZ^{(*)} \to 4\ell$ — the mass “ruler”

Simulated invariant mass spectrum: background continuum (blue, dashed) with a Higgs bump around 126 GeV.

This channel had the sharpest mass resolution (~1.5–2 GeV). Despite low rates, a handful of clustered events near 126 GeV gave ~3σ significance and anchored the Higgs mass measurement.

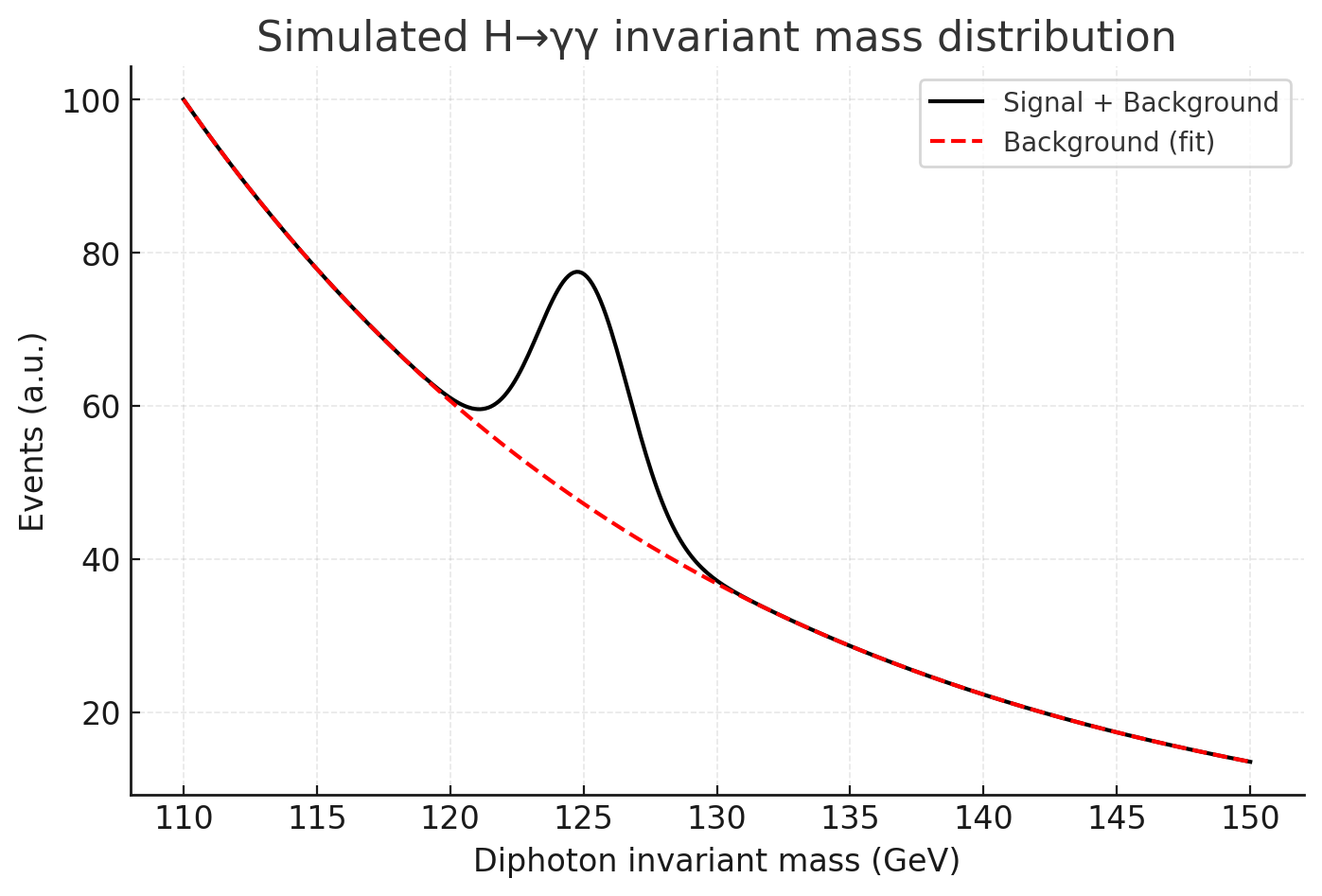

2) $H \to \gamma\gamma$ — the statistical backbone

Diphoton invariant mass: a smooth background (red, dashed) with a clear bump at 125 GeV.

The γγ channel provided ~4.5σ significance on its own. The narrow peak at 126.5 GeV, extracted over smooth backgrounds, made this the most visually compelling and statistically dominant channel in the paper.

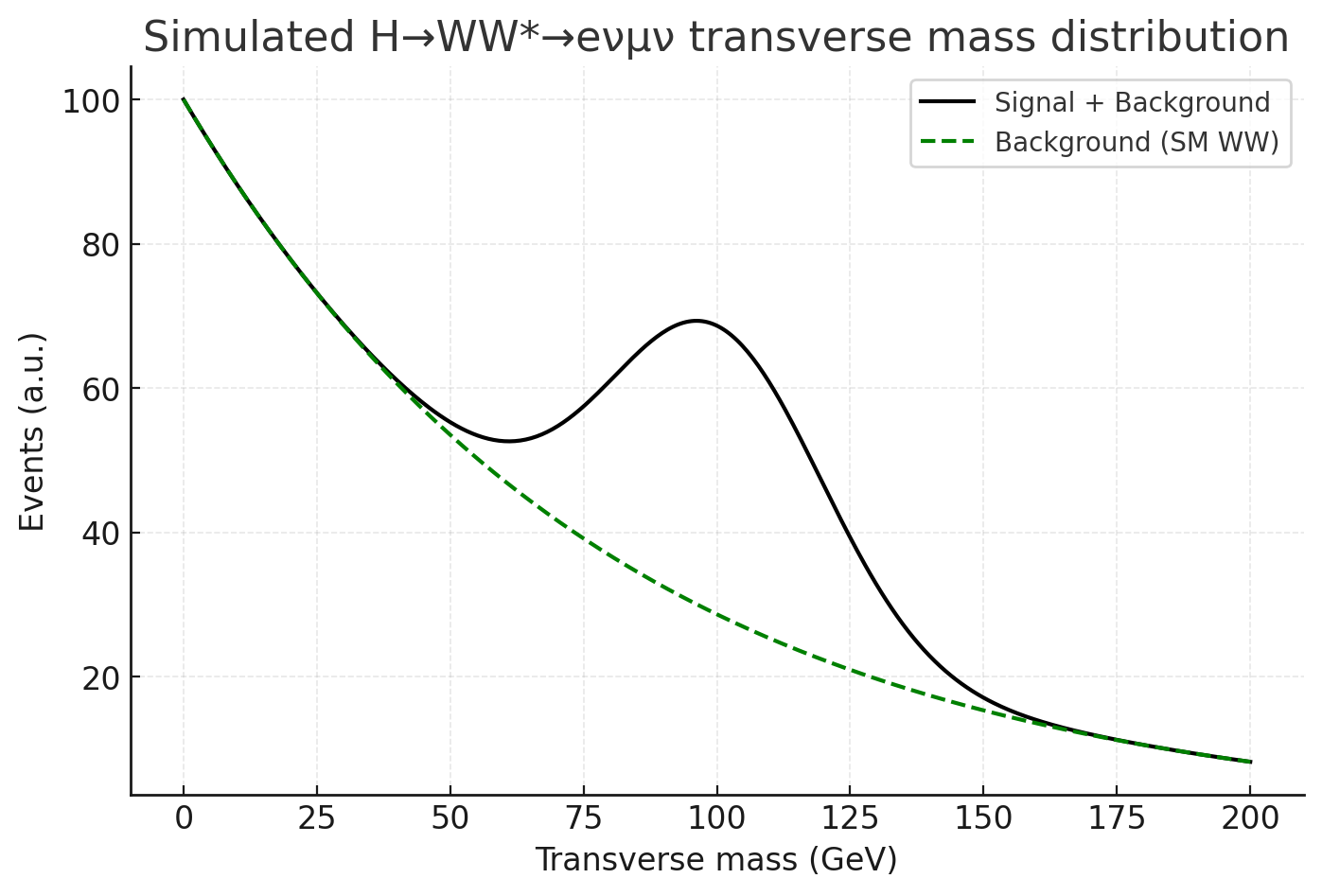

3) $H \to WW^{(*)} \to e\nu\mu\nu$ — the high-rate cross-check

WW transverse mass distribution: signal produces an excess over the falling WW background, but no sharp peak.

This channel, with ~21% branching ratio, delivered statistics but no mass peak (neutrinos escape). It gave ~2σ support and confirmed Higgs coupling to W bosons.

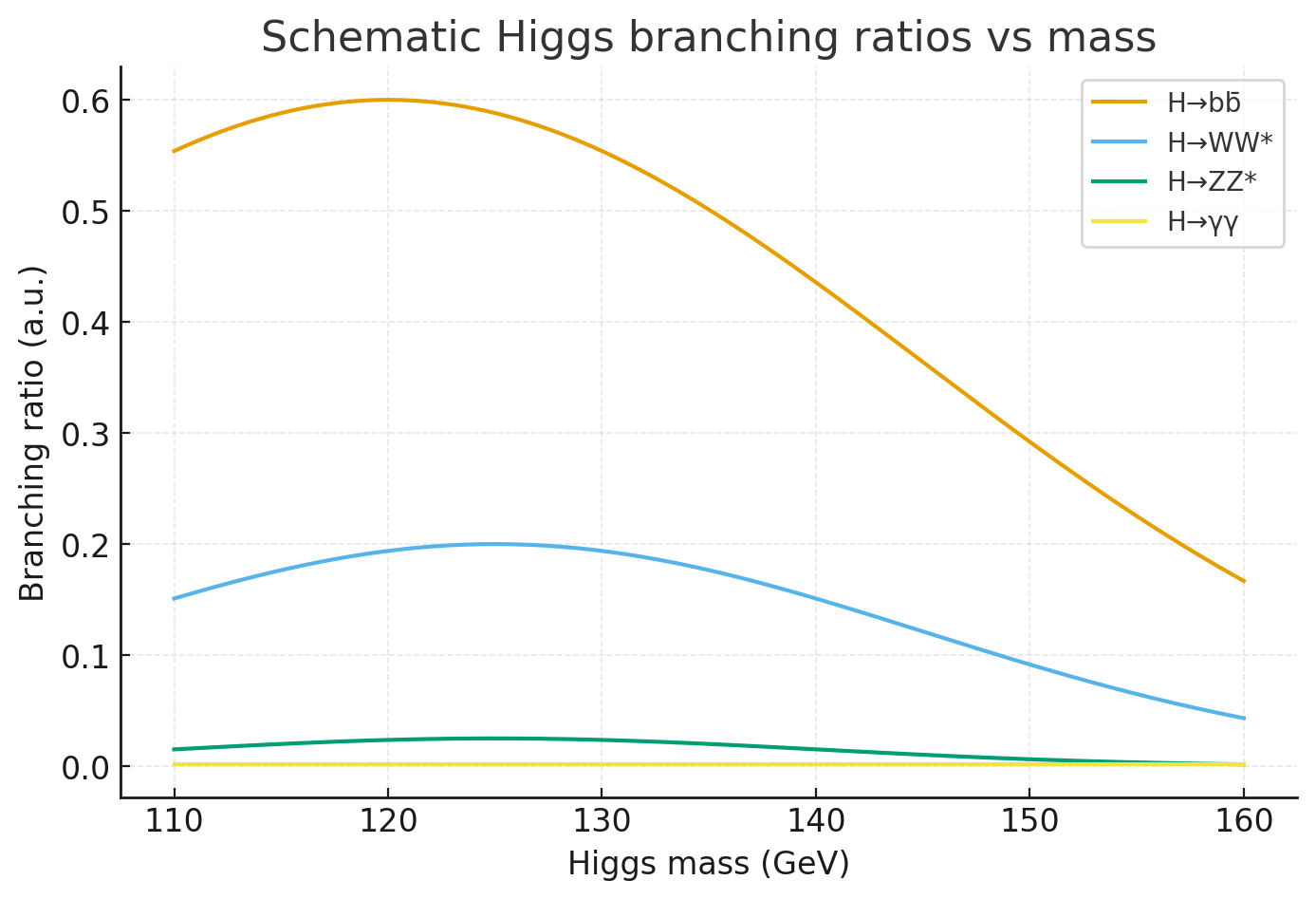

Branching Ratios Context

Schematic branching ratios vs Higgs mass: at ~125 GeV, WW dominates, but γγ and ZZ provide clean, low-background signals.

From Likelihoods to “5 Sigma”

Each channel contributes to a combined likelihood. The global test statistic is the sum of per-channel $q$ values. The result: a >5σ local significance at ~125–126 GeV, with best-fit signal strength:

\[\mu = 1.0 \pm 0.3\]and a Higgs mass around 126 GeV.

Why These Three, Not Others (Then) — and What Changed by 2025

In 2012, γγ and 4ℓ offered precision peaks; WW offered rate. Other key channels were not yet discovery-grade: $H \to b\bar b$, $H \to \tau^+\tau^-$, $H \to \mu^+\mu^-$, and rare modes like $H \to Z\gamma$. By 2018, ATLAS and CMS confirmed $H \to b\bar b$ and $H \to \tau^+\tau^-$. By 2025, evidence for $H \to \mu^+\mu^-$ and refined global coupling fits completed the picture.

What This Paper Solved—and What It Couldn’t

- Solved: Discovery of a boson consistent with the Higgs at ~126 GeV, seen in three independent channels, with production rates matching SM expectations.

- Couldn’t: Determine spin/CP (later established as scalar $0^+$), measure couplings at few-percent precision, or confirm fermionic decays (came with more data).

Closing: From Discovery to a Program

The 2012 paper closed a 50-year gap: the Higgs boson exists, with mass ~125 GeV. But it opened a precision program—testing couplings, searching for rare decays, probing self-interaction. Whether the Higgs remains perfectly SM-like or not, the ATLAS discovery remains one of the most decisive claims ever made in physics: a resonance observed, at >5σ, consistent with the particle that gives mass to matter.

References

- ATLAS Collaboration, Observation of a new particle in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson with the ATLAS detector at the LHC, arXiv:1207.7214