Glitter Isn’t Gold: How the Gold Standard Fails Modern Economics

To many, gold is the ultimate symbol of stability. So why not tie our money to it again? Because when we did, it wrecked the economy — over and over again.

The Allure of Gold: A False Promise

In times of financial uncertainty, calls to “return to the gold standard” often resurface, echoing from op-eds, political campaigns, and even corners of social media. On the surface, the idea sounds responsible, even noble: tie your nation’s currency to a fixed amount of gold, and suddenly you’ve imposed discipline. No more reckless money printing, no more runaway inflation, no more economic meddling.

It’s a system that appeals to people’s instincts — gold feels tangible, incorruptible, and permanent. But those qualities don’t make for a better economy. In fact, history shows they do the opposite. The gold standard, far from being a guardian of stability, was a key contributor to some of the worst economic collapses in modern history.

CPI Under the Gold Standard: Price Chaos in a Golden Cage

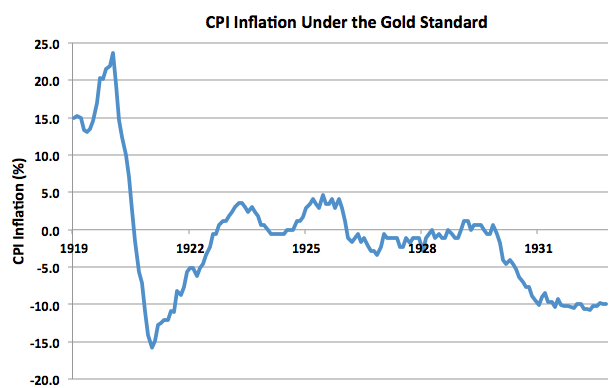

Let’s begin with what proponents claim: that the gold standard promotes price stability. If that were true, inflation would have been flat and predictable during the era when countries used gold to back their money. But the historical data paints a wildly different picture.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries — roughly 1870 to the early 1930s — the U.S. economy operated under various forms of the gold standard. If you examine Consumer Price Index (CPI) data from that era, the pattern is unmistakable: prices didn’t stabilize — they swung violently between inflation and deflation.

In certain decades, like the 1870s and 1890s, prices plummeted. This wasn’t “healthy deflation” — it was economic strangulation. Farmers, manufacturers, and small business owners saw their debts grow more expensive in real terms. Wages fell. Investment dried up.

Then, when new gold discoveries flooded the market — such as the gold rushes in South Africa or Alaska — prices surged. Inflation returned not because of demand or productivity, but simply because more gold was added to the system.

This erratic behavior wasn’t the result of bad policy or poor oversight. It was baked into the system. The gold standard tethered the economy’s fate to a rock dug out of the ground.

CPI Under Quantitative Easing: Stability in the Age of Fiat

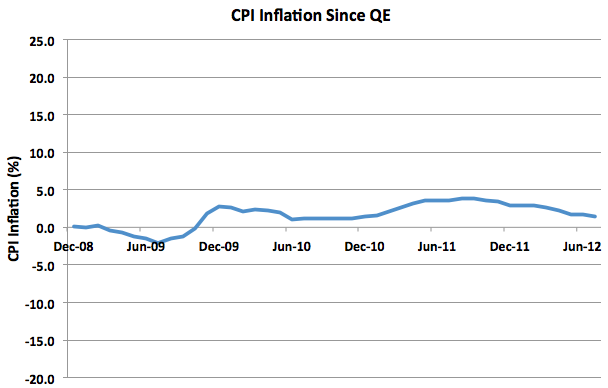

Fast forward to the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The Federal Reserve and other central banks responded with an unprecedented policy: quantitative easing (QE). Trillions of dollars were injected into the global economy in an effort to prevent another Great Depression.

Critics warned this would lead to runaway inflation or even hyperinflation. But the results tell a different story.

Between 2008 and 2012, despite massive monetary expansion, inflation remained modest, hovering close to 2%. There were no wild swings, no deflation spirals, no inflationary blowouts. Just relative calm.

That’s because fiat currency — money not backed by gold — allows central banks to respond to economic conditions in real time. It’s not perfect, but it gives policymakers the flexibility they need to stabilize prices, control unemployment, and smooth out business cycles.

By contrast, the gold standard handcuffs decision-makers. If your economy is shrinking, but you’re running out of gold reserves, you can’t stimulate growth. You can’t print more money. You can’t even lower interest rates without risking a run on your currency. You’re stuck — exactly when you need freedom the most.

Why the Gold Standard Made Things Worse, Not Better

Economies are not clockwork machines; they’re dynamic, living systems that respond to shocks, surprises, and global trends. When World War I broke out, countries had to suspend the gold standard to finance their war efforts. During the Great Depression, the U.S. clung to gold for far too long, prolonging the downturn and deepening the suffering.

Gold advocates often overlook these periods. They imagine a world where governments cannot devalue currencies, but forget that sometimes devaluation is necessary to restore competitiveness, reduce debt burdens, or escape deflationary traps.

A rigid monetary anchor like gold ignores the needs of the real economy. It prioritizes abstract ideals over human outcomes. It may preserve the purchasing power of money in some narrow sense, but it often does so at the expense of jobs, wages, and recovery.

The Persistence of a Bad Idea

So why does the gold standard continue to enjoy support in some circles?

Part of it is ideological. It represents a yearning for discipline — a belief that modern central banks are too powerful, too unaccountable, and too inflation-prone. Gold feels like a way to “take the power back.” Others are simply nostalgic, imagining the past was more stable and prosperous than the present.

But the facts don’t support those feelings. The gold standard didn’t protect ordinary people. It made them vulnerable to distant discoveries, deflationary spirals, and catastrophic recessions. It shackled governments during crises. It failed in practice, not just in theory.

The Verdict: Leave Gold in the Vault

The story told by these two charts — one showing CPI chaos under the gold standard, the other showing stability under quantitative easing — is not a fluke. It reflects a deep truth about monetary systems:

Flexibility beats rigidity.

The ability to adapt, to respond, and to learn from the past is what makes modern economic management work. Central banks are imperfect institutions, but they’ve done a far better job of managing inflation and recovery than gold ever did.

If we want a stable, inclusive, and resilient economy, we don’t need to dig up more gold. We need to rely on tools that respond to reality, not on myths gilded in nostalgia.

References

- Matthew O’Brien (2012). Why the Gold Standard Is the World’s Worst Economic Idea, in 2 Charts. The Atlantic.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/08/why-the-gold-standard-is-the-worlds-worst-economic-idea-in-2-charts/261552/ - Federal Reserve Monetary Policy Reports

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Historical CPI Data